Exploited, Overworked and Organised: How Academics Broke Their Silence

In the spring of 2018, academic workers across the UK took unprecedented strike action to stop their pensions from becoming almost worthless. In the space of just a month, they successfully fought back and exposed a deep crisis in our universities. Now their union is asking its members if they’re prepared to walk out again in what could be a defining battle for the future of higher education. Here, four academics tell us the whole story.

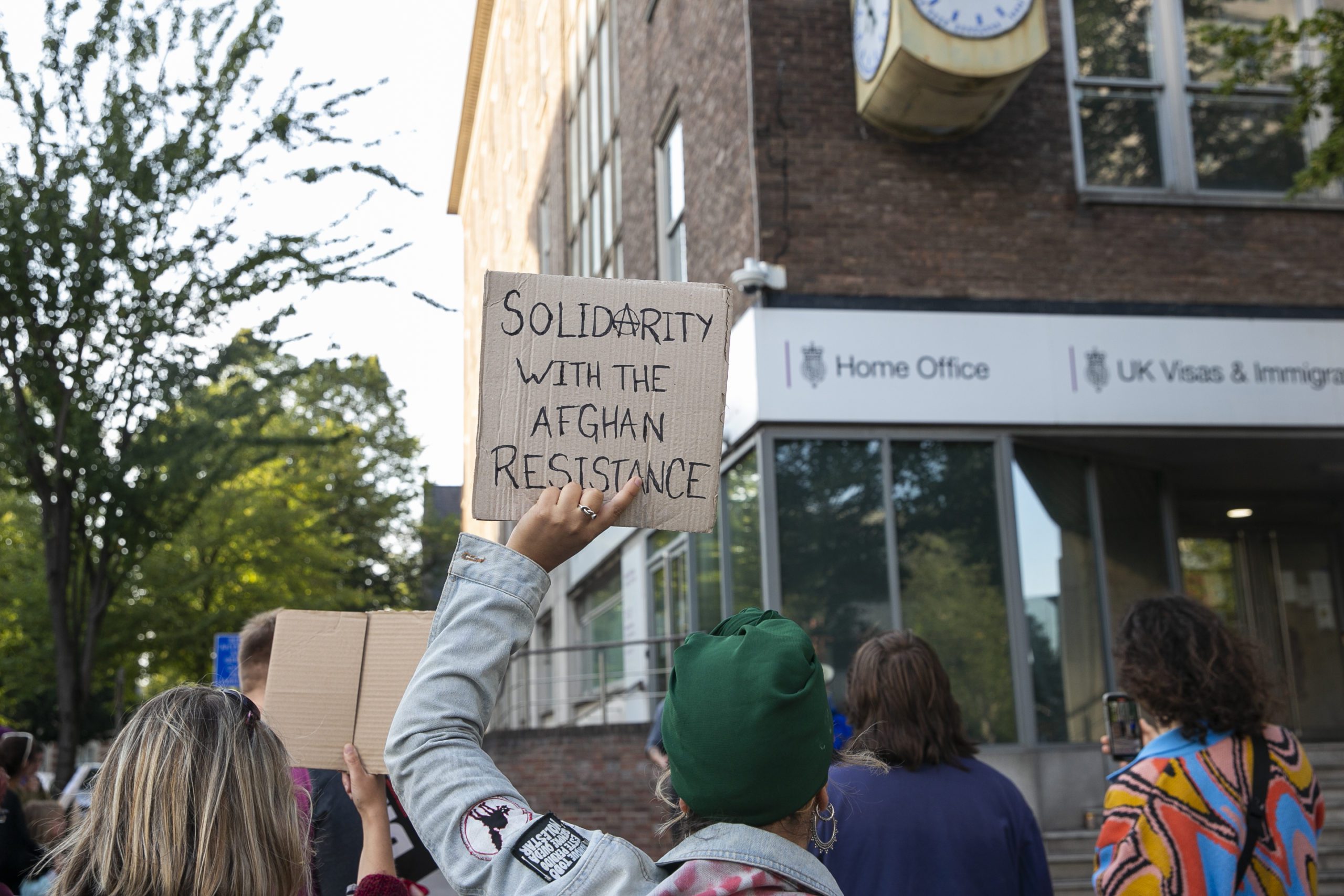

Words by F Clark and SC Cook. Images by V Merkov

September 2019

As a senior lecturer at a prestigious Russell Group university, Steven Stanley is perhaps not the first person that would come to mind if you were asked to picture “trade union activist.” But as we talk after work in a cafe just off the city centre, it quickly becomes clear that circumstance has led him to be just that.

It’s March, and his union, the University College Union (UCU), is asking its members whether they’re prepared to walkout over pay, work insecurity, increasing workload and the threat of redundancy.

“There’s two ballots at the moment,” Steven tells me. “If we get the turnout.., we can strike.”

His own university, Cardiff, is at the heart of this dispute and academics in the Welsh capital are gearing themselves up to face down management over looming job cuts.

“They’ve initiated the third voluntary severance [redundancy] scheme in six years,” he says, holding his cup of tea in his hand. “To try to save money on staff costs, which they think are getting too expensive…”

But the justification for making redundancies is bitterly contested by Steven and his colleagues.

“In 2015 / 2016, Cardiff University took out a £300million public bond,” he explains. “And this was, as far as I know, one of the largest, if not the largest, public bond ever taken out in the history of higher education. And this is to fund their £600million campus redevelopment, which basically involves building a whole new set of shiny buildings.”

One of the main aims of this is to compete for students, or ‘consumers’, as Steven says they’re known as, particularly high-fee-paying undergraduates from rich states such as China. But the plan is already running into trouble. The University has publicly stated that it has a deficit of £20million. This in itself is not disputed, but the reason for the financial shortfall is the subject of intense disagreement.

“[Cardiff University] say the cause of the deficit is increasing staff costs,” Steven explains. “But what our colleagues have shown actually, is that it’s not that staff costs are rising at all. It’s the costs related to the debt that they need to repay the bond with, and also the costs related to the building – what’s called the depreciation of the building- is what’s increasing. And that’s increased something like 70% over a year or two. And it’s those costs that are increasing that we’re needing to pay back.”

The interest on the original government bond Steven is referring to is now a staggering £9million a year. This, say Steven and his colleagues, is what’s really going on: they’re being asked to sacrifice their jobs at the expense of what looks like gross financial mismanagement.

This particular case may only apply to Cardiff, but high risk financialisation, involving enormous building projects and billions in loans, is on the rise across the entire sector. And this is just the tip of the iceberg.

A multitude of issues now faces workers in higher education:

There’s pay and the huge disparity in earnings. “Our VC got a 14% pay rise – £40,000 pounds this year – whilst staff pay has just flatlined,” Steven tells me in exasperation. Workforce casualisation is rampant, and “over 50% of academics in UK higher education are on casual contracts.”

And then there’s workload. “In social sciences,” he says, leaning forward. “I must be doing between two and three people’s jobs.”

“I’m teaching, supervising, doing tutorials, seminars, lectures, module convening, examining, essays, coursework, going on exam boards, supervising PhD students. And that’s just one area of my work, you know. It’s the teaching bit.”

“Then you’ve got research, which if you’re on a teaching research contract, is supposed to be 40% of your time. A lot of academics do [it] in evenings and weekends, or they book annual leave.”

This, he says, involves “writing, reading scholarships, fieldwork interviews, empirical research or desk-based research, bidding for grant money, supervising research assistants, blah, blah, blah.”

It seems so ingrained in his life that he could reel it off in his sleep. “You’re expected to attend departmental meetings, boards of studies…”

And on top of all of this is another worrying development in academia: Steven is now expected to keep tabs on students like never before.

“From attendance through to dealing with student feedback on modules,” he says he must monitor the individuals he’s responsible for.

“You’re supposed to write a report of the module in respect of student feedback and how you’re supposed to improve it for next year. This gets more and more each year as the technologies change and the kind of expectations from government [change].”

“That’s one of the interesting things about UK higher education,” he says, placing his cup down. “Since the 80’s there’s less and less government funding for higher education. But there’s more and more expectation [from government] that we need to account for what we’re doing and have an audit trail and bureaucracy and that’s just insane.”

Compounding these problems is the fact that Cardiff University has gone through at least three voluntary severance schemes in six years, with management seeking yet another round of job cuts. “There’s less and less staff,” Steven says in despair. “The staff you have left… they have to carry more workload.”

On the morning of 19th February 2018, a cleaner working in the library of Cardiff University’s Aberconwy building discovered the body of Dr Malcolm Anderson, a well respected academic who hours earlier had fell through the glass ceiling above.

A husband and father of three, Mr Anderson left two notes before he fell to his death, one of which talked about workload pressure and the extensive hours he was undertaking.

The inquest into his death heard how he was dealing with over six hundred students at the time. And on the day he took his own life, he had 418 exam papers to mark and a day of lectures to prepare for.

Several months later, his wife, Diane Anderson spoke to the BBC about how her husband had tried to warn his employer. “He did tell them,” she said. “In his appraisals he told them that his workload was massive and it was unmanageable but nothing ever changed… it was just more of the same.”

According to Steven, the incident “shocked some of the management into actually trying to address [workload] in some way.”

“But there’s a big problem,” he says. “They’ve just initiated a review of the workload management system. But however much you rework the management system, you’ve got the basic problem with the workload itself. Not the attempt to account for it, or manage it or document it, but the actual workload we’ve got.”

Renata Medeiros-Mirra moved to Cardiff from Portugal in 2006 to complete a PhD.

After being “quite involved” with teaching throughout her degree, she later found herself in precarious work and swamped with marking papers until the early hours. On top of this, she had the responsibility of teaching a core module to four hundred undergraduates and the humiliation of reapplying for a role she’d already been in on a precarious basis.

“When I finished [the PhD] the person who was teaching one big module in the school left [and] I was asked to teach this module – it was teaching statistics to the whole undergrads cohort,” Renata explains. “And I kind of felt a bit like, oh my God, I could just leave tomorrow, you know, and leave all the students at the school in a mess.”

Yet even after knowing her for only five minutes, I know Renata is not the type of person to do this. Alongside her many academic achievements, her online profile states that in 2016 she was nominated for two ‘Enriching Student Life’ awards – Most Effective Teacher, and Most Uplifting Staff Member.

According to Renata, the university “makes perfect use of” not just her own work ethic but that of most academics and employees in Higher Education, and they do so “with no shame whatsoever.”

Sat outside the Embassy Café at Cathays Community Centre on her mid-week day off which she usually reserves for research, Renata seems relaxed as she sips herbal tea and eats a plate of chocolate cake, over which she explains the struggle – and somewhat paradoxical experience – of holding a prestigious role yet being paid by the hour, on a temporary, precarious contract.

“You can’t plan, you really don’t know how much to invest in what you are doing,” Renata explains. “And I think if you care, you’re still going to invest a lot. But you know, it will then be quite a waste of your time. It’s a difficult position to be in.”

Renata reveals that at the end of the academic year, there was still no official lecturer to run the module, so she was asked to continue teaching, and was subsequently put on a temporary one-year contract. But this contract was renewed every year for four years, with Renata receiving excellent feedback from students yet seeing no sign of a permanent job offer in sight.

After four years of teaching the module, rather than changing her contract, the school advertised the role as a vacancy and Renata found herself applying alongside external applicants and, to her embarrassment, a colleague who was teaching on a Masters course in the school.

“They put us in this quite awkward position of applying for a job that I was mainly doing. In the end, my colleague got the role – which, fair enough, not least because this colleague had been in precarious contracts in the School for even longer than I did – but the whole experience was just horrendous.”

Renata is shaking her head as she remembers the stress she was placed under.

“It’s funny how you end up feeling a sense of guilt and shame,” she laughs nervously. “When I found out that I wasn’t going to have the job, my contract was still going on for another five months. During that time, school management would turn their heads away. They didn’t speak to me again after the interviews.”

The psychological toll of working under precarious contracts is something Renata feels very strongly about.

“It does give you a sense [of] ‘it’s my fault, I don’t deserve this and I’m not good enough – otherwise they’d give me a proper job.’”

She talks about the pressure from managers to “do more” to prove her worth and commitment to the university, and while she insists that she personally wasn’t bullied, she recognises that those on precarious contracts often find themselves coerced and manipulated by colleagues or managers.

“You’re so vulnerable to bullying, to working more than you want, or you should, to be doing things that you don’t necessarily want to do, like spending your Saturday at an open day because you kind of feel you need to make yourself more noticeable.”

On the subject of open days, Renata reflects on the marketisation of universities, packaged as places where you can guarantee yourself a good job upon graduating; where everybody is equal and where hard work pays off regardless of where you come from.

“I think we know that actually, if you start from a poorer background, university is unlikely to make you go much further,” she notes.

“You see these students paying tremendous amounts of money and a lot of the time you do wonder, ‘is this the best thing for you, really?’ But then you have to go along to open days, and say, ‘yeah, come to Cardiff, it’s the best place to work. They treat me like shit but it’s the best place for you to come.’”

Renata found herself regularly working at events such as open days in an attempt to strengthen her CV, yet despite this, the impacts of precarity started to eat into every aspect of her personal life, manifesting in an obsessive paranoia: she wasn’t enjoying her free time because she felt like she should be working instead, or doing more to “guarantee” she was “going to get a job.” Everything she did or said was followed with an afterthought of how it would be perceived by her employers and colleagues.

“Even joining a union was a big thing for me at the time,” Renata admits. “It felt like, ‘Gosh, maybe I shouldn’t be doing this because it’s going to potentially undermine my work’ or ‘they might not like me here because I’m in a union.’ You feel like people are kind of looking at you like ‘why are you complaining? You’re so lucky to be here?’”

In the end, Renata secured a part-time permanent position in a different School, something she says made a real difference to her ability to work and her overall well-being.

In her work as one of the UCU Anti-casualisation officers, Renata has been collecting testimonies from colleagues, many of whom have been on non-secure contracts for 10, 15 or even 20 years. These may not always be not the norm, she says “but each case is simply one too many and we must fight this.”

When the University Superannuation Pensions Scheme (USS) announced it intended to move employees from a defined benefit pension scheme, to a defined contribution pension scheme, Andy Williams, media spokesperson for UCU, described it “[as] the straw that broke the camel’s back.”

We meet inside Cardiff University’s futuristic new Journalism school, which sits alongside towering offices in the regenerated central square.

Thumbing through the sheets and resources spread out in front of him, Andy tells me that over the last ten years, staff have seen a fall in their wages of around twenty percent, alongside increasing workloads and unpaid overtime, which he sees as evidence of “McUniversity” – where education is fast, workload high, labour devalued, and marketisation rife.

It was this creeping marketisation, on top of the threat to pensions, which convinced many that enough was enough. In January 2018, UCU members across 63 of the country’s universities balloted in favour of strike action.

“Thankfully, our union grew a backbone,” says Andy. “[They] proposed some quite serious strike action…and that’s because the attack was, you know, very, very serious.”

Pensions experts calculated losses between 40-60% of the retirement income employees were expecting. Putting things into perspective, Andy tells me that he personally would be losing more than half of his pension, taking him from a liveable amount of £20,000 a year, to a shocking £9,000.

“For many UCU members it would simply have meant they would’ve been living in pension poverty,” he says. “And you know, we fought long and hard as workers and trade unionists throughout the 20th century to secure the right to a retirement.”

The USS argued that financial difficulties were the sole reason for the shift in pension schemes, but calculations by pensions experts found this to be a fallacy, and suggested that the USS is more likely to be in surplus, than in deficit. This became known as the “phantom deficit.”

Andy sums it up perfectly: “They tried to pull a fast one on us, really.”

Unfortunately for Universities UK who were pushing the changes, UCU actually had some of the world’s leading pensions experts, who were able to expose the flaws in the USS’ calculations – and blatant lies.

The unveiling of the phantom deficit, and the fact that the case for taking away so many hard-earned pensions was based on a make-believe debt, clearly pushed many to join the picket line.

Scanning his notes for the exact figures, Andy proudly tells me that UCU took on an impressive “16,000 new members across the UK and 400 in Cardiff.” Not all of these were academics who had a pension to defend.

“We attracted those new members during the strike because everybody could see that we were doing it in such a positive [way],” he explains. “People were energised, they were galvanised.”

When the strike kicked off, Carolyn made the decision to join her fellow workers on the picket line even though she didn’t have a pension.

“I was basically supporting the lecturers,” she says when we meet. “My two supervisors were there. Their pensions were in trouble and I had to [show solidarity], because it had nothing to do with me, as a student and the fact that I don’t even live here.”

For Carolyn, A PhD student in her final year who moved to Cardiff from Jamaica in 2013, supporting her colleagues in this way came at the end of a period of union activity and first hand experience of exploitative working practices.

Her funding ran out in 2017, and she found herself having not only to apply for an extension to her PhD, but also to her visa. This meant she had to prove to the government that she had the money required.

“When you extend visa,” Carolyn explains over a cup of hot chocolate, “you must show some funds for every month you are asking for an extension. I was asking for seven months. So I had to have about £7,000 in my account for 28 days untouched.”

“I had to take money from home and whatnot to make [the £7,000] and to keep it there while I still had to be living and eating and stuff.”

In order to survive, Carolyn tried to increase the number of hours she was teaching for the university. But just at this time, management moved to drastically cut the pay for postgraduate workers like herself.

They decided to drastically drop the hourly rate from £19 to just £12. In addition, they announced that the amount of paid preparation time would also be scaled back. “You would get 3 hours [paid prep time] if you’re teaching [a seminar] for the first time,” Carolyn tells me.

“If you’re teaching it for the second time, you would get two hours. Then you would get one hour for every class you teach after that.”

But the new system put in place meant that there would now only be half an hour paid for preparation regardless.

“They were working out that you should take half an hour to prepare and mark, up-script and all that,” Carolyn says in resigned disbelief.

On top of all of this, a lump sum payment – that had been paid to casual teaching staff as a recognition of extra meetings they attended – was abolished.

All of this sparked a wave of anger amongst Carolyn and her colleagues.

“People got kind of militant.” She recalls.

“I stopped attending meetings. It got to the point where when they announced that this and that is going to happen and you will not be paid so people don’t want to turn up.”

Through the UCU, they organised resistance to the plans, which delayed them for a year and forced management to back down from such a severe reduction in pay (it eventually went down to £14 – a 20% cut)

And all of this was sold, Carolyn informs me, on the basis of equalising the pay structure. As is the case in neoliberal society in general, equality only seems to come into play when it results in a net cost benefit to the employer.

Do you feel valued by the university, I ask?

“They would say so by word of mouth,” she replies. “But actions say something else because they fight us so hard.”

“If they valued us in my opinion they would have increased the other students amount and not punished the rest of us by lowering the amount…. it was all a money cutting exercise.”

When the call came to join the strike, Carolyn knew which side of the battle she was on. And unlike previous occasions, the scale of industrial action meant it couldn’t be ignored.

“Whenever there was an attack on our pensions, on our pay, we threatened to strike,” Andy Williams explains. “[But] we’d go on strike for a day, we’d go on strike for two days, one year, I’m ashamed to say we used two-hour strikes – it never worked.

“What made it [different] was the way our members responded to that call to arms, if you like, there was a real unruly grassroots-lead, rank-and-file democracy to this strike, which I’ve never seen as a union member before.”

Along with utilising the expertise of the pension experts, academics from different schools and areas took on different roles. There was a PR team, a media communications team, social media marketing experts, welsh speaking communicators, lawyers, and even musicians who were tasked with “keep[ing] morale up on the picket lines.”

Andy makes the point that many academics are encouraged to use sites such as Twitter often for “marketing reasons” or to promote their own research, yet during the strike, ironically, Twitter was used as a tool against the very institutions that encouraged its use.

“All of a sudden, they’re critiquing their employers, critiquing education policy, critiquing pensions policy, in the most evidence-based and critical way imaginable,” he explains with a smile.

What stands out from the outside, is the solidarity shown by individuals like Carolyn who weren’t directly affected by the pensions – who perhaps didn’t even have a pension to march for at all.

“PhD students, early career academics really joined the strike in force,” Andy tells me. “And they supported the older, more established academics and the fight for pensions that they probably realistically thought they never had a chance of getting themselves, if you see what I mean.”

“They were contesting what higher education could be,” says Steven Stanley. “And really exposing in the process, what it has become: the model of the university as a business, where you’ve got service providers who are the teachers and the staff, and you’ve got customers who are the students.”

“It was really the action of going on strike.. [that showed] how things could be different, you know, in teach outs on the picket line.”

Steven pauses for a moment, admitting that it’s easy to get ‘romantic’ and ‘utopian’ about it all.’

“But it does,” he says, “open a space, and most crucially time where people can be creative, …actually experience joy, real pleasure, you know, just have music, poetry, dancing. Of quite a joyous, carnival-esque kind of feeling …where there was a more fluid boundary between who’s teaching and who’s learning.”

“Of course,” he goes on, again seeking to qualify what he has just said, “We are workers, you know, we’re paid employees and one of the things we do is teach. And so when you think about industrial action…going on strike, you hit this really challenging dilemma, which is, how do you do that with the maximum impact whilst at the same time, not completely undermining your position. And that’s really difficult.”

That difficulty was hit home when Steven and his fellow workers didn’t get the results they were hoping for in the two ballots.

It’s now September 2019, the start of the new academic year and members of the UCU are again balloting for strike action. But while many of the issues on the table have not gone away, something is different this time: they are being joined by other unions in the sector.

UNISON, who represent university staff in administration, cleaning, catering, student support and a host of other services that are essential to a functioning university, are also asking their members whether or not to strike over the issue of pay. If successful, they could join the UCU in coordinated strike action of a sort probably never witnessed in higher education.

With the new trade union bill very much in play however, and the difficulties of getting a high turnout all too real, hitting the required 50% threshold is not going to be easy. Every single member matters and the stakes are high.

But if workers here manage the kind of unified action they pulled off over pensions in Spring 2018, they know they could start to turn the tide of marketisation that has swept across higher education for over three decades.

“This time is different,” Steven says. “Things could actually start to change… there’s a chance.”