In Newport, Women Take Charge Of Huge Relief Operation for Ukrainian Refugees

In the two weeks since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, more than 1.5 million people have been displaced and the numbers are only going up. As well as millions amassing on the border with Poland and elsewhere, there have been scenes of huge crowds trying to get onto trains out of besieged cities. The crisis has spurred on huge numbers of people to help those fleeing the war. SC Cook visited the heart of the relief effort in south Wales.

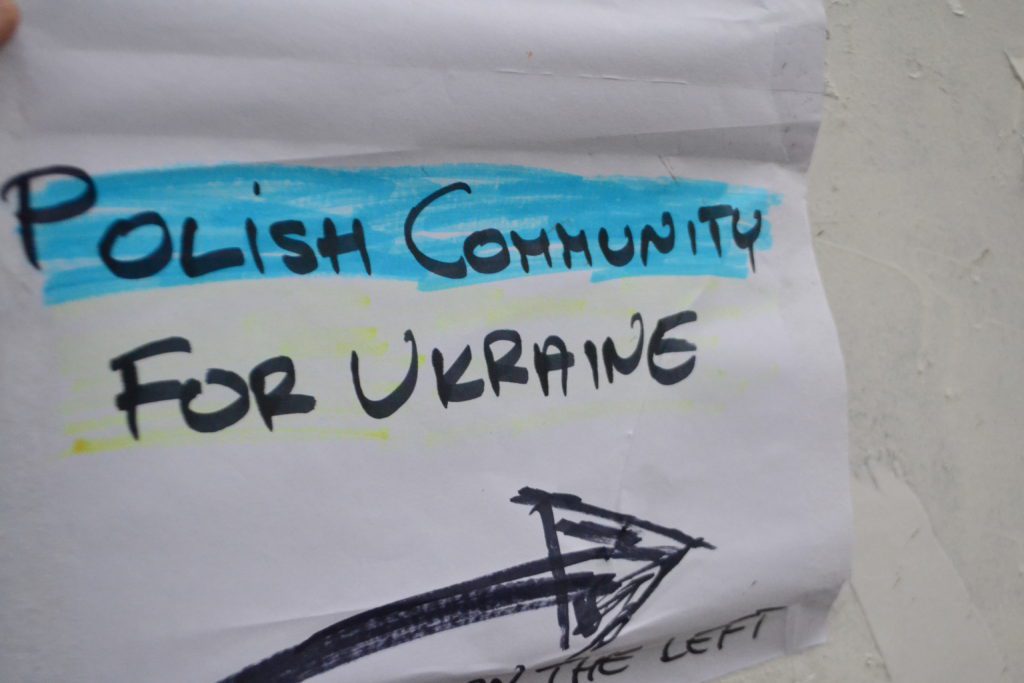

Cover image: Camilla, from Poland: “I’m constantly trying to find more storage because that’s how many donations we’ve received.”

Two weeks ago, Sofiya woke up to the sound of bombing near her home city in Western Ukraine. It was the day that Russia launched its military assault on the country, turning people’s lives upside down in an instant.

Sofiya’s flight from Lviv to Luton was cancelled, so she headed straight for the Polish border crossing instead.

“I have seen the kilometres of queues of people trying to get out,” she tells me as we talk, outside the Newport’s Westgate Hotel on a rainy afternoon, a week after she was forced to flee.

“People were leaving their cars behind and just walking,” she recalls. “Seeing women saying goodbye to their husbands, and kids saying goodbye to their dads because they’re not able to cross the border because they’re the age where they have to come fight…I will never be able to forget this.”

Back in Wales, where she has built a life and a home, Sofiya feels terrified about what might happen to her family back in Ukraine, even though they are not in the area of intense bombing and fighting. This is why she asks for her identity to remain anonymous – Sofiya is not her real name.

“I can tell you that I’m more scared to be here than I was there,” she continues. “I don’t know whether it was because I was running on adrenaline or because I could actually understand what was going on, I could see what was around me…But now I’m more scared.”

“All I do is just rely on phone calls. I’m just waiting for a phone call that the bombing has come to Kyiv, that it’s come to my city. All these times, I don’t know what to think, I don’t know what the plan is, it’s just a very confusing time.”

It’s not hard to see why Maria would be fearful given what has already happened in some parts of the country. The southern Ukrainian city of Mariupol has been a major victim of Russian shelling and artillery fire following the invasion, including the bombing of a children’s hospital.

Thousands have been forced into freezing shelters as Russia’s Grad truck – a mounted multiple missile launcher – caused extensive damage, including to the residential district of Levoberezhny rayon, home to some 170,000 people. Aid groups say the city now faces a humanitarian catastrophe.

In the town of Irpin, just outside the Ukrainian capital Kyiv, a Channel 4 News video appears to show Russian forces attacking families fleeing their homes.

It is this horror that has forced over 1.5 million people to flee Ukraine and seek refuge in neighbouring countries and beyond. The UN has described it as the biggest refugee crisis in Europe since the second world war. Poland has taken in the most people, with almost a million crossing the border from Ukraine in a ten day period.

Images: The Westgate Hotel’s main entrance and sign on the front door directing people to the side entrance.

“I teamed up with my Polish community.”

In response to the crisis, millions of ordinary people have stepped up, offering to put people up in their homes or transport them from the border, usually in Poland, but this kind of reaction has been replicated all over.

When Sofiya got back to Wales, she put a post on Facebook asking people to bring items for Ukrainian refugees. Within a couple of days, she had five full vans turn up. “The kindness has just been surreal, I was not expecting it,” she says.

She quickly got in touch with a group called Women of Newport, who had already begun organising collections for Ukrainian refugees with another group, the Great Orchestra of Christmas Charity

The group, which began by running photography competitions, is headed by a Polish woman called Camilla.

“I teamed up with my Polish community,” she says, explaining how she secured the historic Westgate Hotel in Newport city centre to sort through the donations: “This is our main point, because it’s a big building, lots of space.”

As we talk outside the hotel with Sofiya, she describes feeling “emotional” when news of the Russian invasion of Ukraine broke, “because they are our neighbours and we have a connected history. The Polish community is very much involved because we are next to each other.”

Camilla doesn’t have much time to get into the conflict or her feelings about it, however, she’s too focussed on getting things shipped out. As we talk, briefly in the rain, two Polish men are busy loading up packed boxes of goods to be taken to the Ukrainian border. They have to get things out of the hotel because more donations keep coming in.

In the space of a week, not only was the hotel lobby, its first floor, staircases and side rooms packed with donations, but several warehouses were also already full. In less than six days, they had to ask people to stop making donations because they were almost overwhelmed.

“Every day when we had one storage, one drop off point, the same day it was full,” says Camilla. “I’m constantly trying to find more because that’s how many donations we received.

“So I’m constantly on the phone with someone trying to find more space.”

When you contrast the response of ordinary people to that of the British government, who won’t even waive visa requirements for Ukrainian refugees, you see that anti-migrant politics in Britain really does come from the top.

Image:Kamil and others pack boxes into a loaded van, people inside sort through the donations

“The Polish community and Welsh community came together.”

When I first arrive at the hotel, I am met by Kamil, a Polish man from Cardiff. Before arriving, I was expecting to find a small group of four or five people sorting through items for a few hours a day.

Instead, walking in via the small hotel side entrance, you are met with a huge operation involving dozens of volunteers, all at different stations busily packing boxes, moving things around or trying to not get overwhelmed by the scale of the task that suddenly faces them.

Kamil is visibly shocked by the amount of donations that have flooded in. “Tonnes, and tonnes, and tonnes of donations, I just can’t get my head around it,” he says, laughing almost in disbelief as we try to find a space to stop and talk. “It’s mad, but positive.”

He describes those fleeing the war as “brothers and sisters…you just need to be human at the end of the day, and help each other.” He says people from his home town in Western Poland have been driving to the border to pick up refugees and offer them a place to stay.

In Newport, the Westgate Hotel has become the headquarters for donations across the whole of south Wales. “From Abertillery, the Valleys, Bridgend, Swansea,” Kamil says, before reminding me that all donations have now been called off “because we cannot keep up with the levels.”

At the beginning of last week, they had 20 vans of donations turn up to the Westgate Hotel, by Thursday it was over 40. As well as people giving items, they have also been offering their time and support. Outside, Camilla tells me that she’s received countless messages from people offering to drive the items to Poland. Initially around 20 people were volunteering at the hotel, but by Wednesday last week 120 people came throughout the day, working until 10pm.

One of those is Steve from nearby Langstone. A retired IT worker, he googled what he could do and eventually found himself here, standing in a hotel staircase packing nappies for people he’ll probably never meet. “I’ve got lots of time and just wanted to help, really,” he tells me as he works away. .

Kamil is confident that everything will get to where it needs to go, saying it will either go on planes straight to Ukraine or be driven to the Polish or Ukrainian border by newly recruited volunteers.

“It’s good that as a community, like the Polish community and Welsh community, came together,” he says of the flood of help that’s come in over the past week. “One person is not going to do much, but if you get together, that’s when everything can get sorted.”

Poles make up the largest non-UK migrant community in Wales by some way. Figures from the ONS in 2015 showed there were 23,000 Polish people in Wales, more than double the number of people from the Republic of Ireland and Germany.

Image: Magda, a Polish cleaner who has come to volunteer after her shift: “I am very worried about this situation, and I wanted to cry.”

Many Poles came over to work in Britain following the country joining the European Union in 2004, often in low paid jobs in the hospitality and service sector. They found work across the whole of Wales, including in places like Newport, Merthyr Tydfil and Llanelli. Whilst some left following the vote for Wales and Britain to leave the European Union, many stayed.

One of these is Magda, a 43 year old Polish woman who works for a private cleaning company at the University of South Wales, and who has lived in Wales for the past 18 years.

Magda found out about the operation through Camilla and the Polish community in Newport and has come along after an early cleaning shift. It’s noticeable that like Magda, the vast majority of the volunteers are women, something that the organisers say is reflected in the amount of certain products, such as tampons and nappies, that have come in.

Magda has been particularly shocked by the events because she has family in Ukraine.

“I am very worried about this situation, and I wanted to cry,” she says, describing how those in Ukraine are trying to get to Poland, but as well as facing a huge queue, there are also young children and even a six month old baby to factor into any decision to flee. “Everybody cry,” says Magda.

Her husband’s family in Poland are desperately trying to help by looking for accommodation or offering free lifts.

“Everybody’s scared,” she says. “And we are scared about war in Poland as well.”

“I spoke with my mum and her mother in law in Poland, everybody wants to come here because it’s scary as well.”

“We need to fight the immediate danger that’s happening right now.”

Magda is unsure what can stop the war. On one hand she calls for more involvement from Britain and the West, but also worries that this risks making things even worse by dragging more countries into a military conflict.

Magda’s sense of uncertainty in what could stop the war is reflected in other conversations.

“Putin, he needs to finish it,” says Kamil. “[But] we cannot think about what will happen, we just need to act now…because people will need help anyway. If the war finishes anytime soon, people will go back to Ukraine, and they will have to rebuild the houses and stuff.”

For Sofiya, from Ukraine, when asked if the country could concede NATO membership in return for Russian troop withdrawal, she, like Kamil, says she doesn’t feel qualified to answer that.

Instead, she says “we need to fight the immediate danger that’s happening right now.” For her, this means backing the Ukrainian army and President. She too calls for more Western backing to “stop this from spreading.”

And even though Maria has witnessed the painful scenes of men being forced to say goodbye to their families at the border as they are conscripted to fight, she says that she doesn’t know of any Ukrainian man who doesn’t want to fight.

“They’re all not just willing, they’re ready,” she says. “Just give them arms and they’ll be there. There’s no question..people are doing it with their bare hands, you’ve seen photo footage of people stopping tanks.”

Speaking to Sofiya, it’s not hard to see why the Russian invasion advanced more slowly than Putin and many others expected, given the scale of resistance it has faced.

There are plenty of other stories that echo Maria’s experience. On Radio 4 Woman’s Hour on Wednesday, a reporter described meeting women making Molotov cocktails in a park at night to throw at Russian tanks.

In addition, there have also been incredible scenes of street protests against the Russian occupation. In one video, a crowd can be heard chanting ‘go home’ to Russian soldiers in the newly-occupied city of Melitipol.

But as the conflict drags on, there is also the prospect of a long, protracted war engulfing the whole country, becoming ever more militarised and less about the opposition of Ukrainians to the invasion.

On the weekend, the Financial Times reported how many people are travelling to Ukraine to take up arms, many Ukrainians in other countries, but also foreign soldiers or security operatives.

One person involved in recruiting foreign fighters told the paper that by Thursday last week, 16,000 foreigners had registered an interest in joining the Ukrainian side from Europe and the US, 6,000 of whom were British.

Meanwhile, the Ukrainian army has seen money and arms flood in over the past two weeks from the US, Britain and EU, led by calls from President Zelensky himself. On Wednesday, Tory Defence Secretary Ben Wallace announced that the UK government would send more weapons to Ukraine, including anti-air missiles. Ukraine is now the biggest recipient of Western arms in Europe since World War II, according to The Financial Times.

Even though it doesn’t intend to get directly involved at the moment, the West appears happy to fuel a prolonged conflict in Ukraine and push ordinary people, who want to defend their independence, onto the frontline.

Whilst Ukrainians rightly want the means to defend themselves, the cold reality is that the British government and its allies are not supplying weapons for peace, but with the aim of advancing their own geo-political goals in the wake of the invasion, regardless of the consequences this could bring upon the country and its people.

On the Russian side, Putin has one of the most technically advanced armies in the world, and could possibly try to get additional support from China. He has already shown a willingness to bomb Ukrainian cities and residential areas, something the West has also shown its propensity for in Libya and its backing for Saudi Arabia’s assault on Yemen.

In a scenario of rapidly increasing military escalation, the widespread feelings of solidarity with Ukraine, and the resistance of its people, risk being funnelled into an inter-imperialist war in a country that stands between East and West. All the while, the chance of a negotiated end to the war moves further away and Ukrainian people’s opposition to the invasion gets drowned out.

Such a situation is a world away from the phenomenal organisational effort on display at the Westgate hotel, driven by a commitment to help those in desperate need and whose lives have been shattered by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Asked what her message is to the people of Wales, Sofiya says it is to “keep up the support, keep up the kindness.”

“There’s sometimes news that gets forgotten about. So for as long as the fight is carrying on over there, people need to talk about it.”

All images by SC Cook. This article was amended.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.