“Something Has To Change” – What Is Driving Public Sector Strikes?

The last few months have seen public sector workers withdraw their labour on a scale not seen in decades. After 13 years of seeing their pay fall whilst profits soar, increasing numbers are deciding that they have no option but to strike. Across the picket lines and rallies of these disputes, we spoke to workers on the frontline about what is driving this new industrial militancy.

Written by SC Cook, with reporting by Daryl Peach, Mark Redfern and Adwitiya Pal. Photography by Oojal Kour, Tom Davies and Adwitiya Pal

Sarah Evans had woken up early on the morning of February 1st to brave the cold, windy weather on the outskirts of Swansea.

Wrapped in a warm coat, with a Public and Commercial Services (PCS) union flag draped over the side of her wheelchair, Sarah was on a picket line outside the Driving, Vehicle and Licensing Agency.

Lined up alongside her colleagues on the pavement, she summed up the anger that had driven her and almost half a million others to strike that day.

“We’ve had 11 years of pay freezes and below inflation pay rises, and we can’t take it any more,” she said. “With the cost of living crisis, you’re working full time and you can’t afford to put the heating on. You’re going shopping and having to watch every penny you spend!”

“We’re the government’s staff and we can’t afford to live,” she continued. “It needs to stop. Something has to change.”

It is this powerful sense of anger and injustice that is leading more and more public sector workers to withdraw their labour, and take the fight directly to governments in both Cardiff and London.

On the same day, almost 50 miles east down the M4 corridor, another striking worker, also called Sarah, expressed a similar level of discontent.

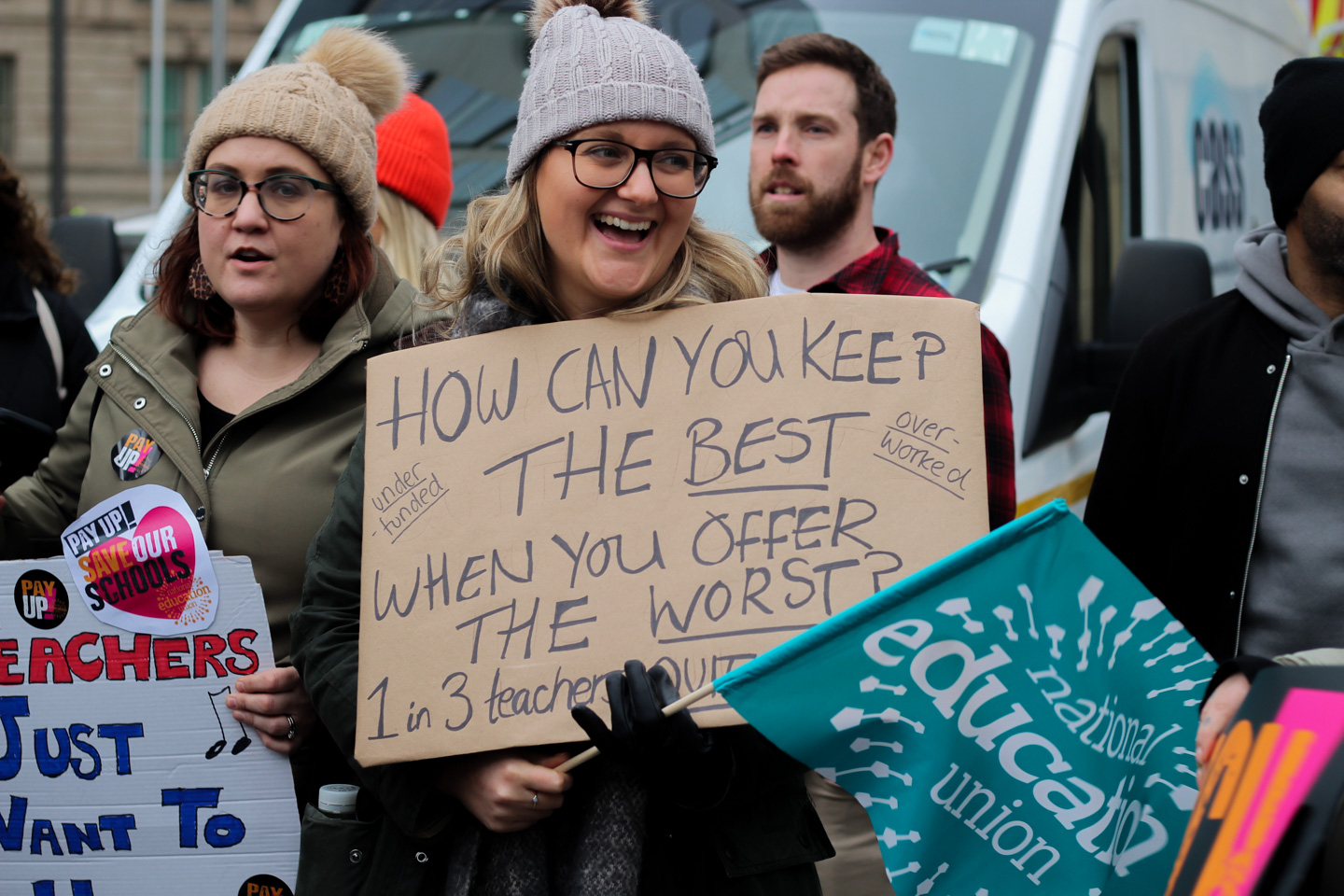

Like around 100,000 other teachers in the National Education Union (NEU), Sarah had decided to strike after witnessing the service she’s dedicated her life to start to fall apart.

“The education system’s at breaking point,” the teacher from St Cadoc’s school in Cardiff said. “There’s only so much teachers can do with such little funding and resourcing in schools.”

“And we’re now at the point where most teachers…” she paused for a moment. “…I don’t know a single teacher not planning to leave the profession. And if something doesn’t change now, I dread to think what our education system will look like in 10 years time.”

It’s a reality that is not only being recognised by other teachers, but also by workers in the public sector more generally, who see that the issue of pay is deeply intertwined with the survival of the service itself.

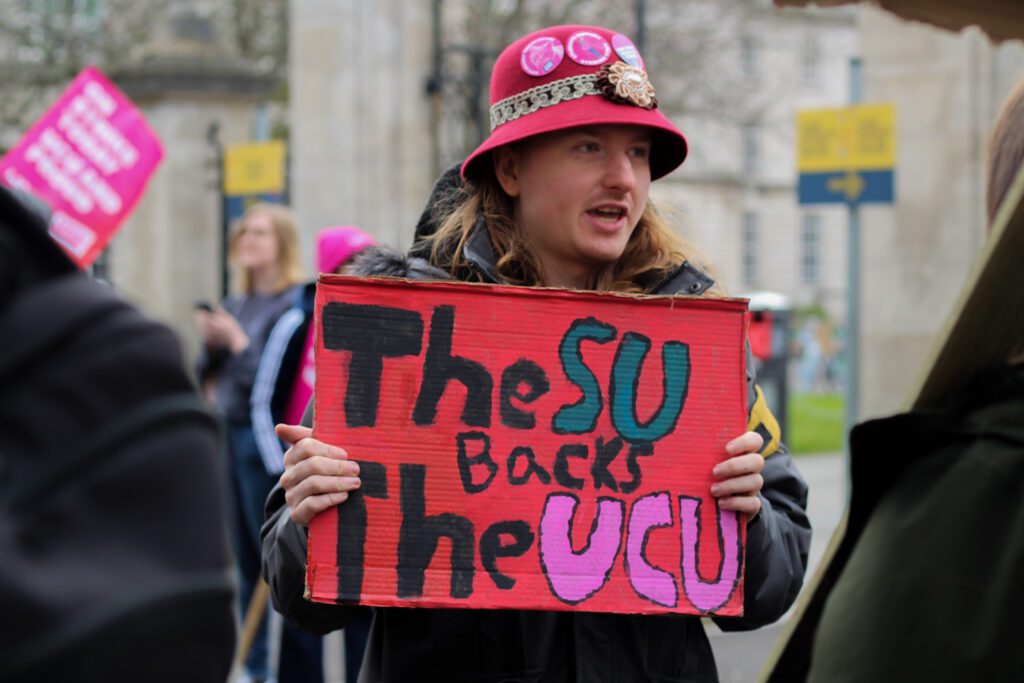

Not far away from where Sarah was speaking, on a picket line outside Cardiff University’s School of Engineering, stood Jane Grieves, a member of the University and College Union (UCU).

“We’re on strike because the conditions of the job here – well of universities in general – have just got so tough,” she told us, whilst giving a thumbs up to a driver honking their horn in solidarity.

Jane reeled off a list of grievances that every worker on strike that day would have found something in common with.

Pay has “massively gone down,” work regularly consists of a “50 hour week,” and as a woman in academia, “I can’t retire until I’m 70 because my pension won’t be enough.”

Then there is a gender pay gap, a racial pay gap, and the enforced casualisation of the workforce, Jane explained: “One of the big problems is, it’s so easy to put people on zero hours contracts…you can be totally disposed of.”

The commonality of what these workers face and the need to fight back together wasn’t hard to see that day. As Jane pointed out, there was another picket line just up the road from her- of Natural Resources Wales workers in the PCS union.

“I think it’s a good idea to make the point,” Jane said, referring to the idea of more coordinated strike action. “Because everybody’s industries are suffering from the same kind of workers not being valued. And like, you know, it’s nothing without us, the trains are nothing without the people who make the trains run, the universities are nothing without the staff…”

The action on February 1st – involving almost half a million workers across the UK and 100,000 in Wales – was the biggest day of joint strike action for over a decade.

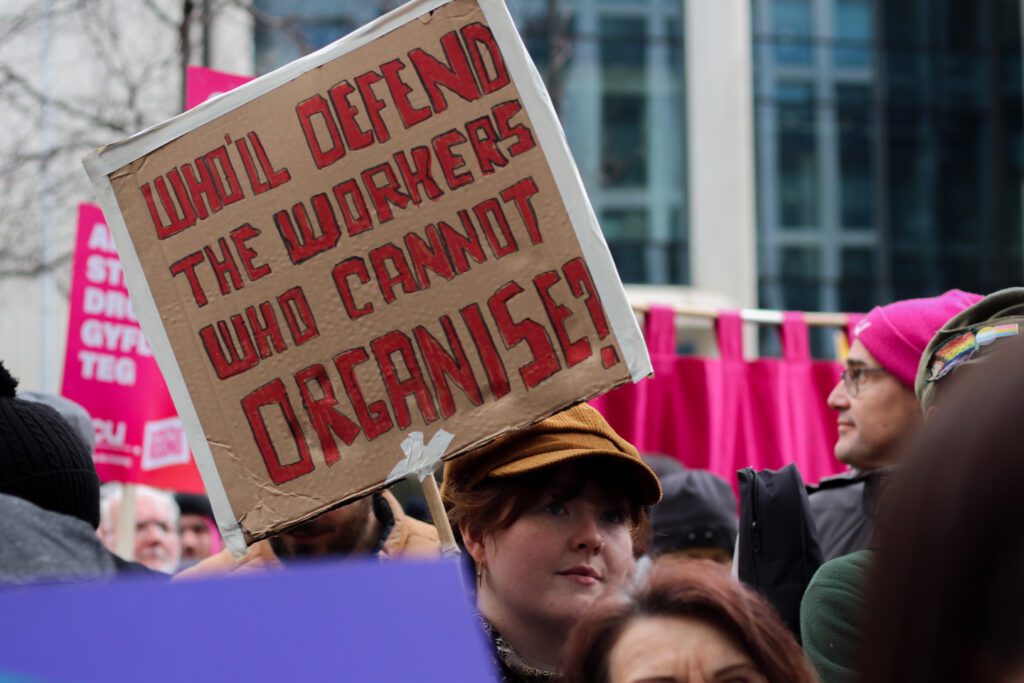

It deliberately coincided with a series of protests called by the TUC against vicious anti-strike laws being rushed through parliament by the UK Government. In Cardiff and elsewhere, hundreds of striking workers from different sectors came together in a show of class unity and strength.

This mood was summed up by Brendan Kelly, a former RMT activist and rail worker who is now a Wales TUC officer.

“They’re frightened of us,” he told the crowd in Cardiff’s central square. “They’re frightened of the power that we possess. They don’t want you to realise that actually, you do produce everything. Without the kind permission of the working class, nothing moves, nothing happens, nothing is produced.”

“We’re not allowed to call for a one day general strike,” Brendan Kelly continued, “but that’s exactly what we do need.”

Workers Show Willingness To Fight

The idea of coordinated strike action has not come from nowhere. Calls for more unity have been growing since the onset of major disputes last year involving the RMT and the CWU.

And given the fact that anti-union laws make it illegal – and therefore unlikely any time soon – for the TUC to call a general strike, coordinated action among unions with strike mandates is seen as the most feasible way of getting close to one.

In the words of the RMT leader, Mick Lynch, “If we can synchronise…it may not be called a general strike but it will look something like a general strike.”

However, despite a motion being passed at the TUC conference last year calling for greater levels of coordination, and several unions having live strike mandates since the autumn, joint strikes have been slow to get off the ground.

Even though there have been days when more than one union has struck together, the walkouts at the beginning of February were the first major instance of coordinated action in the current wave of strikes.

For a lot of workers, especially those in large bargaining groups who’ve seen their pay decimated over the past decade or more, the day could not have come soon enough.

In fact, serious levels of coordination and escalation in strikes are increasingly seen as the only way out of the crisis they find themselves in.

Speaking ahead of 18 days of planned university strikes, the chair of Cardiff UCU branch, Renata Mederos Mirra, told the voice.wales podcast that at a general members meeting with over 100 university workers in attendance earlier in the year, the vast majority backed a proposal for indefinite strike action. In other words, withdrawing their labour and not returning to work until their demands were met.

Renata explained what had driven so many university workers to this point:

“People are just really fed up of losing pay, coming out and feeling like we’re not being heard and nothing is really moving forward so it got to a point when so many people are almost like desperate enough to decide you know what we might just go out and not come in until this is resolved because in the long term that might just get things moving quicker.”

She continued:

“It’s incredible that we got to this point.. This would be unthinkable 4, 5 years ago to have our branch voting for indefinite action. I think people are just coming to a point where everything is just getting so much worse that out of that desperation you feel that you might as well go for it.”

This sentiment was echoed by striking ambulance workers in early February, at the start of a two day walkout by paramedics and emergency call handlers in the Unite union in Wales.

In the face of a new Welsh Government pay offer, which was marginally better than the pay deal already imposed (but still far below inflation), most unions with a strike mandate in the Welsh NHS had called off action whilst they consulted their members on the deal.

But standing in the freezing cold at the Pontprennau ambulance station picket line at 7am, Unite rep and paramedic Richard Tace told voice.wales why his union had gone it alone and not called off their industrial action.

“We’ve had meetings on Friday and meetings over the weekend to put the deal to our members,” he said. “And not a single member has come back and said that they would accept it. Therefore we continue, and will continue to strike until we get a better offer and better conditions.”

At the time, the meetings were the only gauge of how health workers were feeling about the new offer, which was an additional 1.5% on pay and a 1.5% lump sum.

Richard described the mood which had led Unite members to swiftly reject the deal:

“Our job is to save lives. We all know that when we join the NHS it’s not that we’re not going to make millions, but you would expect when you’re working full time to be able to live…I do really believe that we are doing the right thing [in striking].”

Richard himself is on such a low wage already that the latest offer wouldn’t even have touched the sides:

“We’ve seen a number of our colleagues pass away due to contracting COVID-19. And, you know, we’ve, we’re trying our best, it’s really hard to, to live at the moment given that we don’t really get much money. You know, I’m on the bottom of my [pay] band. So just to try and keep a roof over my head and put food on the table for my children, I have to work overtime.”

What’s Driving The Strikes?

It is this experience of being at breaking point in a grossly unfair system which is hardening workers’ resolve when it comes to withdrawing their labour.

Another reason is that workers are seeing some of the impressive victories won by their counterparts in the private sector, and taking inspiration from this.

“Everybody is in the same boat” says Sarah Evans, the DVLA worker in the PCS union. “No matter where you’re working at the minute. Everybody needs a pay rise. The private sector, we’re seeing them having a 9,10,11% pay rise and we’re not asking for much. We’re just asking to be treated fairly…it’s got to stop. We’ve got to do something and this [striking] is hopefully the way we’ll get the government to listen to us and take us seriously.”

But there are other, longer term factors at play too.

As the paramedic Richard Tace alludes to, the experience of working at the height of the pandemic has also had a significant role in not only showing workers their collective power, but also how they can be sacrificed as individuals.

In the background of all this is the 13 year assault on living standards through the drive of austerity. Workers have been spun a series of lies by every government since the financial crash of 2008, all designed to suppress their pay.

The biggest of all of these was that if public sector workers accepted pay restraint in the early 2010s, it would help the government pay off the national debt and the pain would be temporary. But now, 13 years later, their pay is still being cut under false pretences.

In this period, it’s not just pay that has been stripped back. The entire social state, staffed by these very same workers, has also been decimated.

As the teacher Sarah put it, if something doesn’t change, the education system she has dedicated her life to will fall apart. NHS workers say the same about the health service.

The assault on local government and public services means that workers don’t want pay rises to come from existing budgets that are already empty – a move which effectively pits staff against other resources.

This is why the NEU is calling for a fully funded pay rise in an attempt to break down the government’s position.

“When the government says that they’ve offered us a 5% pay rise, which was obviously below inflation,” explains NEU member Sarah, “that’s not funded, that’s coming from school budgets.”

“We want a fully funded pay rise that comes from the government, not from school resources.”

Justifying these attacks has been the consistent refrain from government that money is tight, and ordinary people must suffer as a result. But here too, the spin has unravelled.

Workers are seeing for themselves how energy firms are announcing obscene profits – £32bn for Shell, £3.3bn for Centrica, £23bn for BP – which all have come directly from their own wages as they’re forced to pay over the odds on their energy.

And to make matters even worse, these very same workers are being told that their pay must be held back in order to tame inflation, yet the real cause of soaring inflation – overcharging by energy firms – is left untouched.

The Politics Of Pay

For all these reasons, it is impossible to remove politics from the strikes and try to make them limited to just pay.

This is certainly the case in Wales, where workers are facing down two governments at once.

On the one hand, like their counterparts in England, they are dealing with a Tory government in Westminster determined to hold back their pay and push through even more austerity.

And on the other, they face a Welsh Labour government trying to impose this punitive funding settlement on workers in Wales.

When it comes to Westminster, Sunak’s administration has attempted to dig in and hold public sector pay rises to around 5% or under, far below inflation and many of the wage rises won by workers in the private sector.

Even in disputes with private companies, such as rail, the Tories have worked to stop better pay deals being won, less they provide an incentive to other workers to go on the offensive.

In the words of Brendan Kelly, a former rail worker and RMT officer, Rishi Sunak has effectively “nationalised the dispute” by subsidising the rail companies during strike days so as to alleviate pressure that might otherwise force the companies to concede to rail worker demands.

Against this backdrop, workers have consistently delivered thumping votes to strike in education, transport and health, and the fire, mail and the civil service sectors among others.

But it is also the case that the Tories want to smash any serious attempt to build working class unity. This is what’s behind attempts to make it illegal for certain workers to even go on strike at all.

Coordinated strikes are something the Tories fear as they know it will ramp up the pressure on Rishi Sunak and make workers harder to pick off in groups, something which is undoubtedly part of the UK government’s strategy.

The divide-and-rule tactic was evident in the move to bring only the RCN into pay negotiations whilst excluding the other health unions who would normally be involved.

In Wales, the Welsh Government has long played the role of implementing whatever budget settlement gets handed down to it from Westminster with little in the way of public resistance.

Only this year, as strikes have escalated, has Mark Drakeford shown any signs of meaningful frustration over austerity.

However, Welsh Government had hoped it could end the disputes with a new offer of an additional 1.5% for this year’s pay deal – bringing the total to about a 6 or 6.5% pay rise – and a one of payment worth 1.5% of annual pay.

All unions engaged in industrial action against the Welsh Government, except Unite, called off the strikes whilst they consulted their members on the new offer.

Welsh Government might have thought their strategy to end the strikes would succeed.

But it quickly began to unravel. The NEU initially declared that its members had formally rejected the deal, then this was swiftly followed by Unite, the GMB and finally the RCN.

Even though the health strikes have been paused for negotiations, it all points to greater levels of animosity between public sector workers and the Welsh Government than we’ve seen before, making it harder for Mark Drakeford’s administration to contain the disputes.

Challenges Facing The Strikes

Through large strike votes, increasing numbers of workers are showing that they are prepared for major confrontation, deciding that the way forward is through serious industrial action in an attempt to smash the pay strategy of both the government and employers.

In this context, workers appear to be in no mood to accept paltry pay rises or lump sum payments that will be eaten up by a couple of months worth of gas bills.

But trade union leaders themselves are also under pressure to match the growing militancy shown by their members, and won’t easily be forgiven if they demobilise strikes when workers want to move in the opposite direction.

This was seen in the reaction of large numbers of UCU members to the decision of the union’s General Secretary, Jo Grady, to call off two weeks of strikes to enter negotiations with university bosses, and without having secured a credible offer.

“What democratic process was followed by UCU in making this decision?,” wrote Sol Gamsu, Branch President of Durham University UCU. “This is egregious. It is no way to run a dispute. If you want to alienate and infuriate your reps that are absolutely crucial to running your dispute this is exactly how to do it.”

Equally, when news broke that the RCN called off its planned two day strike in England in order to enter negotiations without the other health unions, it was met with unease and confusion by many rank and file members, who feared it would result in no credible offer whilst also weakening workers’ bargaining power.

An open letter from RCN members to the union’s leadership called for the planned industrial action to stay on whilst negotiations took place, as well as greater levels of coordination with other health unions.

As the letter stated:

“We did not go on strike for a below inflation pay rise, and to call off strikes for negotiations around this amount is disrespectful to members who have sacrificed much and taken great risks, and to the public who have had their lives disrupted by our strike.”

As these tensions emerge, it gives rise to a small but developing rank-and-file organisation within the labour movement.

A natural point where worker’s anger could come together is 15th March, on budget day.

An event which has long been associated in the minds of public sector workers as a day when their pay is devalued once again, strikes and protests on this day could be particularly galvanising.

Walkouts announced for that day so far include 100,000 civil service workers in the PCS union, up to 300,000 members of the National Education Union and some 48,000 junior doctors in the BMA, after more than 98% of them voted to strike with a record turnout of 77.5%.

Joining them will be 70,000 members of UCU across 150 universities, and possibly firefighters in the FBU, among others.

Calls for the day to involve greater numbers of workers have been led by the NEU and PCS unions. In an open letter, leading members of both unions lead calls for major coordination:

“We believe ‘unity is strength’ and that trade union members across the movement with their friends, families and supporters coming together on budget day in London will apply huge pressure on the government above and beyond what we can do as separate disputes.”

What is becoming clearer is that workers are moving towards industrial action with a speed and determination not seen in years, often at a faster pace than their own union leaders are prepared to go.

Any serious level of coordination will likely come from this growing militancy among workers at a grassroots level. There is, however, few guarantees of this happening. Given that each strike is working to its own schedule and set of negotiations, they can be called off at any moment, sometimes taking out a large chunk of workers who could otherwise be involved in a joint strike.

“We’ve got no option but to be here.”

As more essential workers withdraw their labour and services are inevitably affected, the question of wider support will be poised more sharply than before.

Polling has been highly favourable to the strikes, and there is a sense that now is the time to escalate the fight against the government.

But even if the polling wasn’t favourable, many of those withdrawing their labour are still aware of the power they have.

“Our contact centre is practically closed because so many staff have gone on strike,” DVLA worker Sarah Evans said proudly on the morning of February 1st. “

We’ve seen the numbers going into the office, its minimum. There’s hardly anyone going in. There’s usually queues out here of staff waiting to get in. We haven’t seen that today.”

“We’ve got no option but to be here,” she continued.

“It was payday yesterday and most people like me have got the bills coming out today. If they’re lucky they’ll be left with a little something, but it’s not much. It’s not enough to last the month. When you’ve got the government’s own staff having to claim benefits just to top up their pay, that shows that what the government is paying us isn’t enough.”

Ultimately, that is the attitude which is pushing these strikes forward. And for the first time in years, many workers are realising the power they have.

voice.wales is a vital alternative to the mainstream media. Whilst most publications want to keep the status quo intact, we work to challenge it. We survive with the help of our monthly subscribers and don’t have big-money corporate backers. If you can afford £3 a month or more, join us now to secure the future of alternative and radical media in Wales. Click here to join or go to https://www.patreon.com/voicewales

If you want to support us directly, please email [email protected]

Image gallery by Oojal Kour, Adwitiya Pal and Tom Davies (scroll for images)