Ukrainian Nationalists Distorted The Truth Of My Great Uncle Gareth Jones – Now The Senedd Is Too

As the Welsh Parliament prepares to mark Ukrainian Holodomor Memorial Day, Philip Colley, the great nephew of Gareth Jones, the Welsh journalist who brought the man-made famine to the world’s attention, argues that truth is being sacrificed on the altar of nationalist interests.

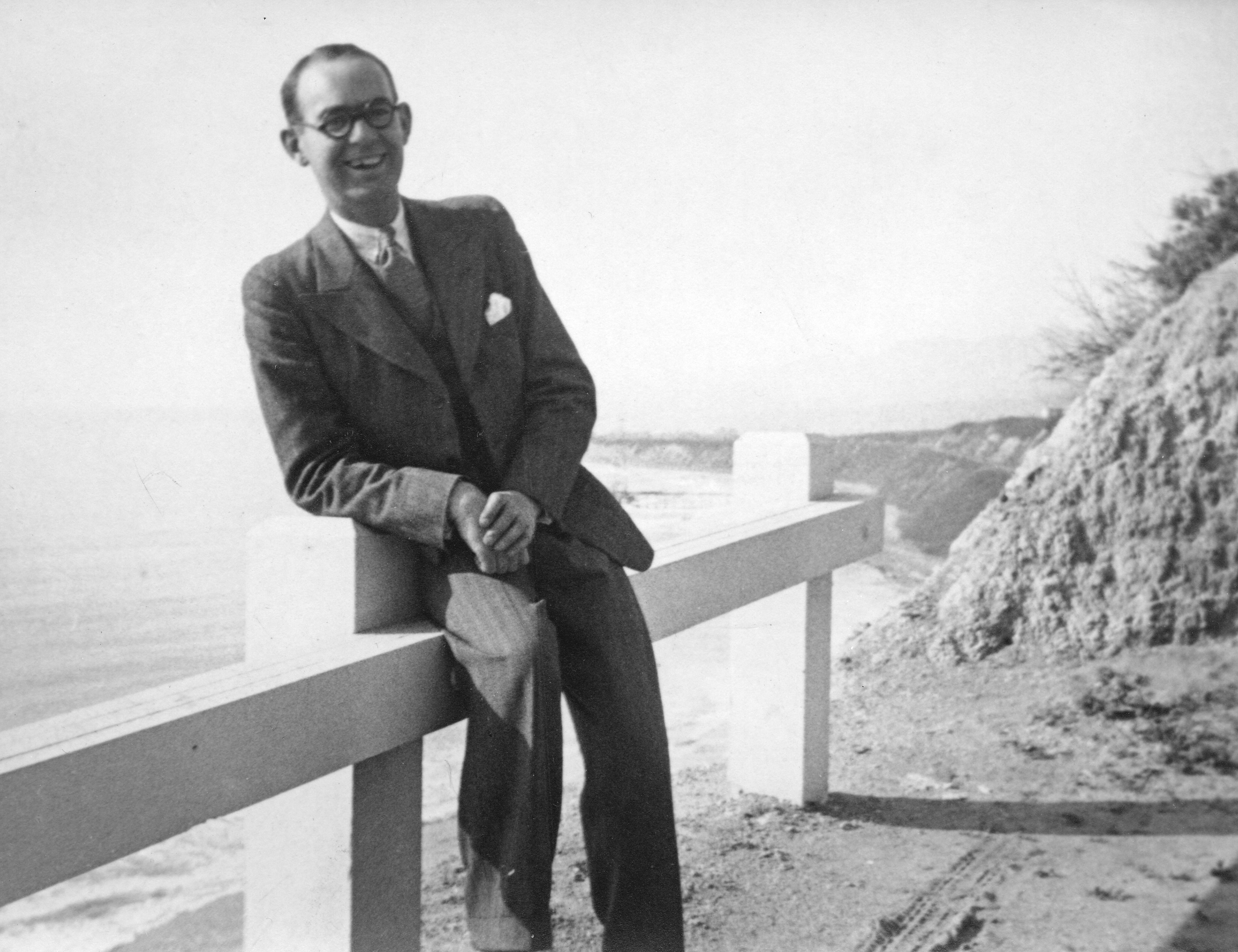

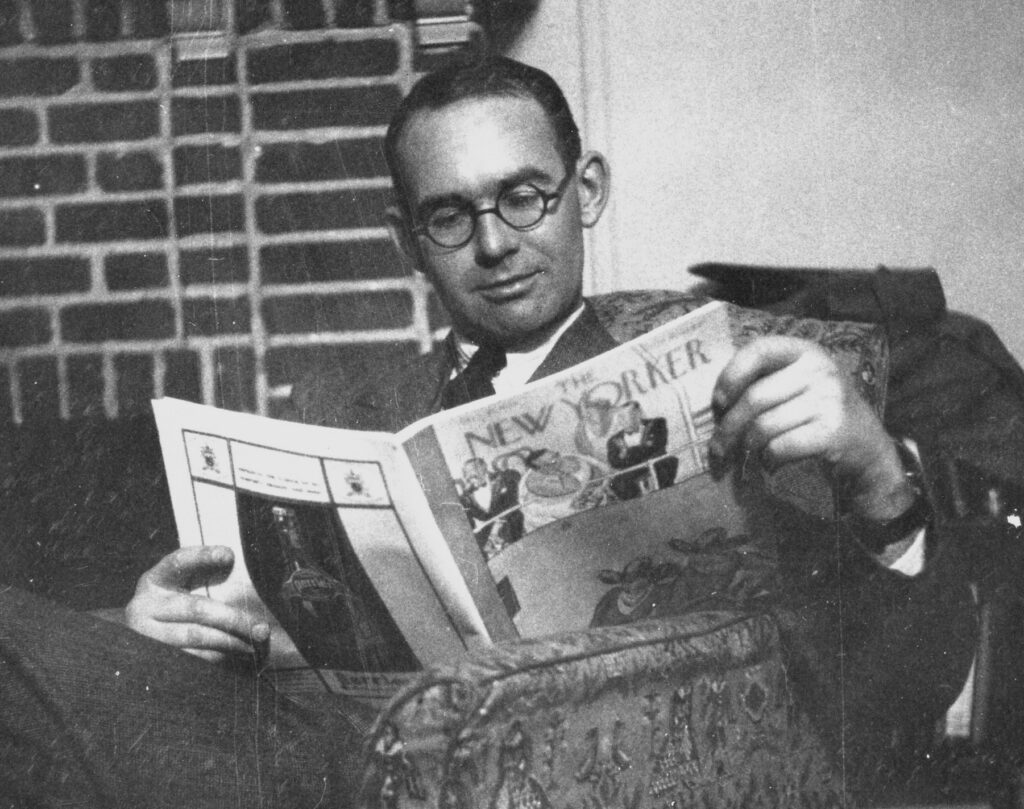

By Philip Colley. Cover image, Gareth Jones, courtesy of the Gareth Vaughan Jones Estate

The Welsh Parliament is to commemorate my great uncle, Gareth Jones on the 25th November as part of an event in memory of the horrific famine that took place in Ukraine in 1932/33.

Gareth, one of Wales’ greatest journalists, was instrumental in bringing that famine to the attention of the world, but the person being commemorated is not somebody I recognise. What they appear to be honouring is a myth created by Ukrainian ultra-nationalists who have refashioned the truth of Gareth’s story, not least through the film Mr Jones, to fit in with their own nation-building and in the context of the Russia – Ukraine war.

The famine Gareth reported on, now known as the Holodomor, was declared to be a genocide by the Welsh Senedd on the 25th October in an emotive session but one that was entirely political and devoid of any serious historical analysis. It was also one that misrepresented Gareth’s story.

After Gareth’s murder in 1935, like the Great Soviet famine he reported on, Gareth was forgotten by the world, but not by his family. From a young age I was regaled with stories about a clearly special relative from his surviving sisters, my grandmother Eirian and my great aunt Gwyneth. From my mother, too. She had worshipped her uncle and never really came to terms with his untimely death. As a retirement project in 2000 she began researching his story and writing his official biography More than a Grain of Truth. What she found out, my brother Nigel put online.

Through the web, Ukrainian ultra-nationalists from the diaspora soon became aware of all this and got in touch with the family. They immediately saw that Gareth was a key witness, and his diaries crucial evidence, for a famine the existence of which their political foe, the Soviet Union, had consistently denied.

Their discovery of Gareth coincided with the start of a ‘memory management’ campaign begun in 2004 by the then President Yushchenko in which he sought to provide the newly independent Ukraine with a new, national story.

The Soviet view of Ukraine’s history was jettisoned and in its place historical myths fostered over the years by the diaspora ‘were elevated to state policy’. One aim of this campaign was to try and airbrush out of history the accepted historical fact that the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUNb), led by the fascist and anti-Semite Stepan Bandera, and its armed wing the UPA, had not just modelled themselves on the Nazis but had also collaborated with them in the murder of 1.5 million Ukrainian Jews, and also slaughtered countless Poles.

Ukrainian ultra-nationalists who had hitherto rightly been vilified for the mass murder of Jews were suddenly turned into national heroes, with accompanying statues and torchlit parades in their honour. The second, main, aim was to persuade the world that the Holodomor was an act of genocide despite the fact that many respected historians did not consider that to be the case.

And inconveniently, when properly analysed, nor did Gareth’s testimony. That is why through plaques, hagiography and film those ultra-nationalists have gone to such great lengths to hone and repurpose Gareth as a political tool to better fit their task. It often feels to me that while Gareth was kidnapped in life by bandits, in death he has been kidnapped by Banderites.

Another aspect of Gareth’s story often now conveniently forgotten is the inescapable truth that his journey to Ukraine in 1933 was only made possible by an invitation from diplomats of the newly elected Nazi government in Germany. Gareth was no fascist but I have written more about this in Le Monde.

When all this began, our family knew little about Ukraine, less about the history of Ukrainian nationalism and nothing at all about that nationalism’s chief vehicle between the wars, Stephan Bandera’s OUNb. One of course cannot have anything but sympathy for the nation of Ukraine in its current plight today. But the Ukrainian nationalists back in Gareth’s day were certainly not nationalists in the benign Welsh sense.

Bandera’s aim was to set up an ethnically pure Ukrainian state completely cleansed, by whatever means, of all its Jewish, Polish, Russian and other non-Ukrainian citizens. His organisation fashioned itself on the Nazis in everything from the Führer principle (Führerprinzip) to anti-Semitism right down to mirroring the Hitler salute.

As Gareth noted the famine inflicted on Ukrainians, far from suppressing nationalism, swelled the nationalists’ ranks. At the time, thanks to Nazi and OUNb propaganda, much of the blame for that famine was pinned on the Jews and what was termed by many anti-Semitic critics of the Soviet Union as ‘Judeo-Bolshevism’.

So, when the Nazis arrived in Ukraine in 1941, and the Soviets fled, it was not hard for them and their collaborators from the OUNb to stir the local population into helping take revenge on those that remained. The pogroms and killings began in Lviv in June and carried on throughout Ukraine until by 1943 much of its Jewish population no longer existed. When the tide of war turned at Stalingrad and the Soviets came back, many Ukrainian nationalists, often with Jewish and Polish blood on their hands, were forced to flee along with the Nazis.

Many joined the existing diaspora in Canada and America, some even went to Wales, where they and their descendants have been articulate and forceful in continuing to promote the OUNb agenda. Few were brought to justice.

When some members of the diaspora, including nationalist historian Lubomyr Luciuk and even Stepan Bandera’s grandson, came into their lives in the early years of this century my mother and brother had no idea who they were dealing with. Indeed, they were flattered to be feted, and delighted that Gareth was finally beginning to get the recognition that history so clearly owed him.

While some were genuinely grateful for Gareth’s work, others had broader aims in mind. My mother and brother were flown back and forth across the Atlantic and accommodated at some expense as foot soldiers in a campaign to spread the diaspora narrative about the ‘famine-genocide’. They were given opportunities to speak to prestigious bodies, including the UN. But there was a price to pay. The truth of Gareth’s story began to be chipped away. The people involved had a serious political agenda and when my mother eventually refused to go along with their ways of ‘memory management’, their tactics became vicious. It’s a long story but, for opposing what she saw as the ‘politicisation’ of the man that only she actually knew, my mother was ostracised and bullied by her newly found ‘friends’.

In the end our family became split and broken, arguably like Ukraine itself today, on the altar of Ukrainian diaspora memory politics.

The issue that caused that split was one of the many myths that have grown up around Gareth, namely the idea that his murder by bandits in Inner Mongolia in 1935 was engineered by the Soviet NKVD as revenge for his reporting on the famine. That theory fits in perfectly with the image of him as a martyr that now reigns in Ukraine where the mythologizing of Gareth has caused him to attain an almost Christ-like status. My mother needed evidence. But there is no actual evidence for that theory and what evidence there is generally points to the conclusion that it was a kidnap unrelated to the Soviet Union that went tragically wrong. Gareth was warned by two different British military attaches, as well as the Chinese authorities, under no circumstances to go to the Manchukuo border area as it was infested by bandits. But tragically, for all of us, he ignored their advice.

Another myth fostered is that Gareth was only reporting on famine in the Ukraine. In terms of proportion of the population, apart from Kazakhstan, that is without doubt where most of the deaths occurred in one of the most unimaginably distressing events in history. But millions also died of starvation elsewhere, including in Russia, and though it seems to have been deliberately forgotten now, Gareth reported on their suffering as well. “Tell them we are starving”, the title of a book of his transcribed ‘famine diaries’, is actually based on a plea from a German colonist. In truth he was a hero for all the victims of Stalinism at the time, Russian as well as Ukrainian.

“Even twenty miles away from Moscow there was no bread”, he wrote. As well as what he saw in Ukraine he provided witness statements from starving Russian peasants from Nizhny Novgorod and Crimea, then part of Russia before it was gifted by Khrushchev to Soviet Ukraine in 1954. In fact, much of Gareth’s famous 3-day walk through the starving countryside, depicted in Mr Jones as being solely in Ukraine, actually took place on the Russian side of the border. He slept the first of his two nights in the Soviet countryside in a Russian collective south of Belgorod where they were “looking forward to death” and he reported seeing the distended stomach of a Russian child “belly swollen”. The next day, the last devastated, breadless village he passed through before leaving Russia was Krasny Khutor, shelled by Ukraine last September and reportedly attacked again by Ukrainian militia in a cross-border raid on the 20th May of this year.

When Gareth left Moscow at the end of March 1933 he gave a press conference in Berlin where he made clear that in his opinion the famine was “everywhere” in the Soviet Union. The first newspaper report that emerged from that conference quoted him as saying “Everywhere was the cry, ‘There is no bread. We are dying’. This cry came from every part of Russia, from the Volga, Siberia, White Russia [Byelorussia], the North Caucasus, Central Asia.”

As well as in Wales, there have also been two debates in the UK Parliament recently about whether to declare the Holodomor as a genocide. Three times the above quote by my great uncle has been used, but each time the last sentence was omitted to imply that Gareth was just talking about Ukraine. Of course, such historical distortion by our parliamentarians is wrong. That is probably why, for all its other faults, the British Government itself has refused to recognise it as genocide. Its “long-standing policy” being that “any judgment on whether genocide has occurred is a matter for a competent court”, not a parliament.

In the October 25th debate which preceded the Senedd decision to recognise the Ukrainian famine as genocide,there was little or no attempt to engage in any serious analysis or explore the nuances of such a complex historical event.

It was without doubt an appalling humanitarian crime, but the jury of historians remains very much out as to whether it was genocide. Nonetheless the word ‘genocide’ was mentioned some 24 times as if the mention of it was enough to prove their point. The word ‘collectivisation’ however, without which it is impossible to understand the catastrophe itself and which Gareth saw as its chief cause, didn’t appear once. The level of input from some MS’s could be characterised as little more than ‘this was a genocide because we say it was’.

Like the Senedd itself, I am not qualified to pronounce on whether what happened was technically genocide. But it is my duty to speak out when politicians misuse Gareth’s testimony to imply that it was. Gareth reported that Stalin wanted to coerce the peasants into collectives for the sake of what he thought was agricultural efficiency and for his drive to full-scale industrialisation. But, particularly in Ukraine, the peasants in huge numbers refused to accept collectivisation, and that led to what was effectively a war between them and the state. It was a war which the state, through its cynical weaponization of the food supply, was destined to win. Gareth wrote:

“What was the cause of the famine? It was man-made. It was the result of the Soviet Policy of collectivisation, which went completely against the mentality of the Russian peasant… And when the Communists took the away the land, they revolted and would not work, a policy which led to an epidemic of weeds and to the crop failure of 1932-3…they took the bread also by the raiding parties from the towns which despoiled the countryside of food and by collectivising the cattle they deprived the peasant of the ownership of his cow – and remember that a cow spells wealth and happiness to the peasant. Finally, collectivisation robbed the peasant of liberty and reduced him to the status of a serf. No wonder that the land population retired to the stove and refused to go out to the fields unless driven by the bayonets of the troops.”

This was Gareth’s contemporaneous view, rooted in reality and his understanding of the situation, as opposed to the somewhat simplistic assessment by MS Alun Davies that Stalin just wanted to “eliminate the rural population of Ukraine.”

Listening to the references to Gareth in the Senedd it is worrying that knowledge of his work appears to come chiefly from a film, Mr Jones, that fictionalises his story almost beyond recognition. It is of course far easier in this post-literate world to watch a film on BBC iPlayer than it is to delve into the complex history of the famine but surely, we should expect better from our representatives.

What is particularly galling is that the person lauded by the Senedd for bringing us the knowledge of Gareth is the journalist Martin Shipton. The person that the Senedd should have thanked was my mother, Dr Margaret Siriol Colley. It was her tireless efforts and sacrifice over many years that led to Gareth’s official biography, the book which inspired Mr Jones. If it had not been for her, the world might still not know about him. Mr Shipton published his book some 17 years after her invaluable research, a biography for which, incidentally, the relevant copyright permission was never sought.

Sadly, my mother always feared she too would be airbrushed out of history, and it appears the Welsh establishment has done just that. Just like 90 years earlier when her beloved ‘Uncle Gareth’ was airbrushed out of history by the English establishment.

During the Holodomor debate MS Alun Davies informed the Senedd about the recent unveiling of a third Gareth ‘political plaque’, this time at the national library in Kyiv. What he didn’t tell them was that the guest of honour at that event was the Holocaust revisionist Volodoymyr Viatrovych, who was sacked in 2019 by President Zelensky for his attempts to rehabilitate Nazi collaborators.

In an act of great disrespect Viatrovych used the event to invoke “the spirit of Gareth Jones” as inspiration for his acts of historical distortion. Even more shocking is that at the same event a so-called “Gareth Jones Medal of Truth and Honour” was awarded posthumously to one of Ukraine’s most notorious anti-Semites the white nationalist, Levko Lukyanenko, an admirer of David Duke and someone who once claimed that the Holodomor was carried out by a “satanical” government controlled by Jews.

As part of the November 25th event in The Senedd the organisers are considering showing a video of the unveiling event. Out of respect for the Welsh Jewish community, and Gareth’s memory, I hope they don’t and have written to the Llywydd to request as such*. The Senedd would be wise not to let its admirable sympathy for a country at war cloud its judgement and allow itself to be used as a platform for some deeply unsavoury characters.

Lubomyr Luciuk, who recently co-authored a book with Viatrovych, was behind the plaque in Kyiv, as he was behind two other similar plaques to Gareth, in Barry and Aberystwyth. He is, according to the Friends of Simon Wiesenthal Centre, a person who “continues to spread Holocaust distortion and disinformation”. I cannot help but wonder now whether those plaques are compromised by their association with Ukrainian ultra-nationalists and historical distortion, not least when it comes to the Holocaust. The truth of Ukraine’s past must be addressed honestly, as must the truth of Gareth Jones and his testimony. In my opinion, this is the very least we can do to properly honour his legacy.

*Following publication and representations from the family, the Senedd has now agreed not to play any part of the video.

Guest post by Philip Colley, Great Nephew and Literary Executor of Gareth Jones. No part of this article is to be syndicated or reproduced without express permission of the author.

Ending Dependence On Russian Gas Is Really About Hooking Europe To US Gas | Carys Hopkins